Creating the liveable buildings of the future: with forward-thinking planning, flexibility, and a focus on user needs

Climate protection, rapidly rising energy prices, and the mood of the times require us to rethink building planning and construction. Even energy guzzlers like air conditioning systems can in some cases be offset by using alternative systems. Sören Eilers, Project Consultant at GEZE, and Marco Sperling, Qualified Architectural Engineer at PPP Architekten Lübeck explain how liveable buildings of the future might look, and how users and clients can be persuaded of the benefits of new systems.

Buildings are constructed in the present, for the future

What is a 'liveable building', anyway? In the past, houses were simple buildings where people primarily slept and ate. Today, buildings need to do more: “We want to feel good in them, have a place to rest, be able to move without barriers, and ideally also live sustainably. It not only creates a space, but must also fit users and their needs – both today and into the future. Only then can we call a building a 'liveable building' explains Sören Eilers.

Stipulations have changed significantly, even in just the last 15 years: People's mindset has changed, and there are also regional differences when it comes to what makes a building modern. While some areas build only passive houses, the focus in others is on free learning concepts and open spaces, for example. For planners and architects, that means thinking far ahead.

Buildings are constructed in the present for the future – for the next 30 to 50 years of use. That means we need to consider potential uses a couple of decades from now even in our current planning. However, budget is almost always the limiting factor.

Marco Sperling, Qualified Architectural Engineer, PPP Architekten Lübeck

But that alone is not enough. In addition to the framework conditions set out by the client, there are various statutory stipulations, standards, and regulations to comply with. The different regulations can also deviate from one another widely. “In Germany, almost everything is regulated. Often, the client’s framework conditions are negotiable, but this is much more difficult with statutory stipulations,” as Sperling knows from experience. To ensure that all stipulations, needs, requests, and regulations are met simultaneously, intensive coordination with everyone involved is essential: “The need for coordination is ever-increasing, and is even embedded in certification processes. It makes sense if we want to ensure the final building is a good one. And it's always the case that the better the coordination right from the start, the better the results!” Ideally, all the expert planners involved for building services, structural engineering, supporting structure, etc., installation companies, as well as users, the client and their representatives would be involved.

The regulations governing that coordination must be determined in consultation with the client.

Each building must be planned individually based on its specific use. © Jürgen Pollak / GEZE GmbH

Many planners and architects see on a daily basis that there are so many regulations now that there are no longer clear stipulations. “With so many standards, we're often unclear abut what we are actually supposed to be doing,” says Sperling. “The specifications derived from technical regulations, for instance on building ventilation, are massive. Specifications from the Technical Workplace Regulations 3.6, for instance, have some information on indoor air quality. So do those in DIN EN 16798 or VDI 6040. However, all of them stipulate different values and variables for the same topic. That means we have to coordinate during planning with our clients on which regulations are used as the basis for the specific project.”

Because, says Sperling, one thing is clear: “There is no single solution for all applications. Architecture is always prototyping! Each building is planned and constructed for the individual location and purpose. Each one has different stipulations that define in each case what is planned and implemented. Of course, we always assume a building will maintain the same type of use. But it doesn't have to!” Very topically, the pandemic and the debate on the use of gas triggered by the war in Ukraine show that the future always brings change. “Good, liveable buildings have to be able to offset this, and adapt.”

A building not only creates a space, it must also fit users and their needs – both today and into the future. Only then can we call it a 'liveable building'.

Sören Eilers, GEZE GmbH Project ConsultantLiveable buildings need to be adaptable to users’ needs

Often, the comfort of subsequent users is down to subjective factors.

Even in the planning stage, it is important to consider potential uses decades into the future. © GEZE GmbH

However, regardless of the need to comply with regulations, planners always need to keep the human factor in mind. Field studies have shown that users’ sense of comfort in buildings is not always dependent on measurable variables like the right humidity and temperature. Instead, subjective and seemingly less important things like the way a user feels in a room are what make a difference. “One trial was carried out, for instance, with a control system for a mechanical ventilation system ,” reports Marco Sperling. “The room in question was air-conditioned and set to the ideal temperature, with everything centrally controlled. However, users felt uncomfortable. Only when the building was retrofitted to install controllers and thermostats that people could set themselves did their sense of comfort improve – simply because they had the opportunity to change things.” From his viewpoint, therefore, it is a good idea for liveable buildings to maintain users’ ability to influence their surroundings, using as much technology as needed, but as little as possible.

“This automatically results in hybrid systems, such as hybrid ventilation systems,” says Sören Eilers. Their strengths include, for instance, the potential savings they offer in terms of energy consumption and costs. As Marco Sperling continues, hybrid systems that make it possible to switch off a machine and regulate fresh air intake manually, for instance, would offer the greatest potential savings. “There are many things that cannot be defined in advance, but that depend on user behaviour. If building owners want to take advantage of funding programmes, the focus is always on energy efficiency.”

Hybrid systems: Simple and smart, but often unknown

The planning needs to consider rising energy prices, concerns surrounding climate change, and the mood of the times. © Jürgen Pollak / GEZE GmbH

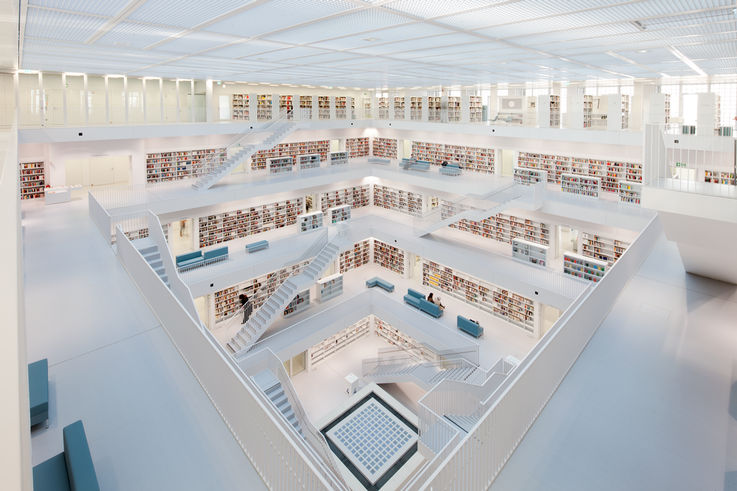

In any case, experts say that intensive discussions on the advantages and disadvantages of a hybrid system are always a good idea, even in the planning stage. “Often, you will need to convince those involved. Because of this, we take outings with users and clients before planning, do on-site workshops, show them different buildings – all so that they understand how we envision buildings. This allows us to show what rooms, ventilation concepts, etc. can do, and how our plans can be implemented. This works well: Acceptance increases greatly when you see how well architecture, aesthetics, usability, surface quality, indoor air quality, and the ability to convert the building to a new use work together. "And this acceptance among users and building owners is essential to make buildings constructed today liveable and viable into the future.

Buildings must be able to react flexibly to circumstances like the power supply, climate change, and unfortunately to events like wars and pandemics as well,” according to the experts. The result: “So we have to work with everyone involved to define goals today that will allow us to create buildings that will still function well in 50 years."

Marco Sperling, Qualified Architectural Engineer, PPP Architekten LübeckWhat is a hybrid system?

To put it simply, a hybrid system is a mix of automated and manual components. Most of the components in a hybrid system would be installed in a building anyway, meaning they do not result in additional work. A hybrid ventilation system, for instance, can consist of windows that the building would contain anyway. A mechanical exhaust system is then added to these. Fresh air enters through the manually opened windows. “There are many different ways for air to infiltrate into the room,” says Marco Sperling. “What's important is that systems need to communicate with one another.”